We contain genetic multitudes

By understanding microchimerism, we open new horizons for personalized therapies against autoimmune diseases and pregnancy complications.

Microchimerism is derived from the Greek words “micro” (μικρός) meaning “small” and “chimera” (Χίμαιρα) based on a fire-breathing hybrid creature of Greek mythology composed of different animal parts. When adopted by biologists, microchimerism is simply small cells inside your body that are not your own.

When do we see evidence of microchimerism?

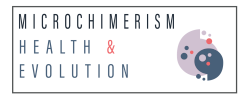

Microchimerism occurs via two main modes: naturally (microchimerism caused by natural means) and artificially (microchimerism caused by human intervention).

Pregnancy: is the most common cause of natural microchimerism, in which cells are exchanged in both directions between mother and fetus through the placenta or amniotic fluid.

Types of natural microchimerism:

- Maternal microchimerism: transfer of maternal cells into the fetal circulation during pregnancy or parturition,

- Fetal microchimerism: transfer of fetal cells into the maternal circulation during pregnancy or parturition,

- Microchimerism between twins: exchange of cells between twinned fetuses in utero.

Types of artificial microchimerism:

- Medical procedures: can lead to microchimerism occurring artificially, typically due to blood transfusions or stem cell and organ transplants.

- Transfusion-associated microchimerism: transfer of cells accompanying blood transfusion,

- Transplantation-associated microchimerism: transfer of cells from the organ or stem cell donor to the host.

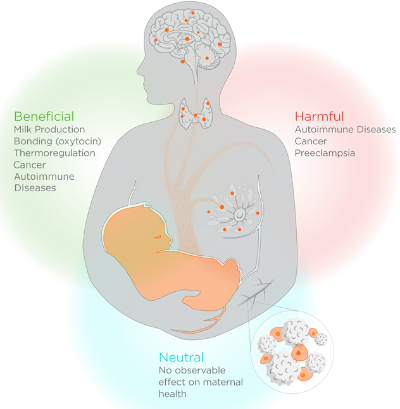

What are the consequences of microchimeric cells in the body?

Microchimeric cells have been found as multiple cell types in many tissues in the host body and can persist in an individual for decades – potentially even for the host’s entire lifetime. Microchimeric cells are shown to be implicated in:

- Maternal wound healing,

- Immunological protection for the developing fetus,

- Pregnancy complications (e.g., pre-eclampsia, spontaneous abortion),

- Offspring autoimmune disorders,

- Potential transgenerational effects, such as the presence of grandmother cells in grandchildren.

Why is microchimerism so hard to study?

For the past 50 years, research has led to contradictory results as to whether microchimerism contributes to health or disease. Contradictions in the literature are partly due to:

- Limited microchimerism detection methods available,

- Sample bias toward women who have given birth to sons; reliance on the presence or absence of Y-linked alleles to differentiate between maternal and fetal cells,

- Limited reporting of microchimeric cells (i.e., presence or absence of microchimeric cells),

- Low microchimeric cell counts relative to the total number of cells in the body (i.e., microchimeric cells are relatively rare among the totality of an organism’s cells).

Interested in learning more about microchimerism?

Then you might find the following article in the journal TheScientist intriguing:

“A Stranger to Oneself: The Mystery of Fetal Microchimerism.”